African Politicians: Modern-Day Social Media Influencers of Fame and Fortune

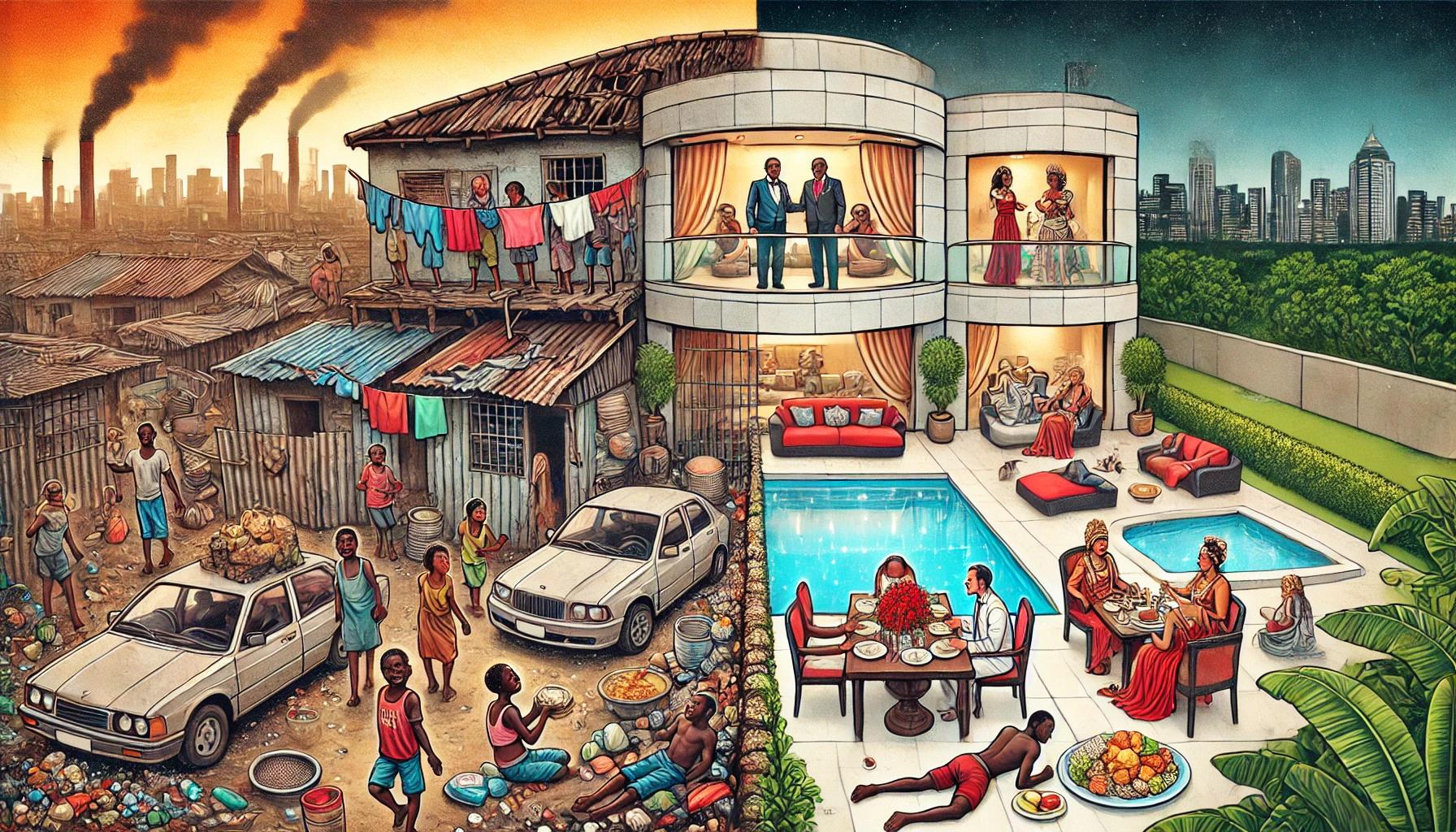

In recent years, many African politicians have embraced social media as a tool to bolster their public image, amass followers, and project an aura of influence. They present curated snapshots of development projects, humanitarian gestures, and charismatic moments. However, behind these glossy façades lies a stark contrast: the reality of stagnating or deteriorating socio-economic conditions across the continent. While their social media platforms may reflect prosperity and progress, the lived experiences of their constituents often tell a different story.

Emotional Intelligence or Emotional Manipulation?

Emotional intelligence is a crucial trait for leaders, allowing them to connect with their followers and inspire hope. Yet, many African leaders have weaponised this trait, using it to manipulate public sentiment. For instance, Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni, in power since 1986, regularly uses platforms like Twitter to portray himself as a champion of development. Despite his claims, Uganda continues to face significant challenges in healthcare, education, and corruption. According to Transparency International, Uganda ranked 142nd out of 180 countries on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) in 2023.

Similarly, Paul Biya of Cameroon, one of the longest-serving presidents globally, uses his social media to showcase achievements while remaining largely absent from his country for extended periods. Despite being in power for over four decades, Cameroon faces economic stagnation and widespread human rights abuses. Amnesty International has documented forced disappearances and unlawful detentions of opposition leaders and activists, painting a grim picture that contrasts with Biya’s social media image.

Democratic Elections or Silent Dynasties?

In countries like Equatorial Guinea, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo has ruled since 1979, often using elections as a façade for democratic legitimacy. His son, Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, is being groomed as his successor, effectively establishing a dynastic monarchy. The 2016 elections, which Obiang claimed to have won with 93.7% of the vote, were widely criticised by international observers for being neither free nor fair. Opponents of such regimes often face imprisonment or worse. For instance, in Rwanda, critics of President Paul Kagame’s regime, such as the late Patrick Karegeya, have mysteriously disappeared or been found dead under suspicious circumstances.

The Luxury Lifestyle Behind Closed Doors

While many African leaders publicly portray their nations as struggling and in dire need of Western aid, their lifestyles often paint a starkly contrasting picture of opulence and extravagance. One prominent example is Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea. Despite his country’s widespread poverty—where over 70% of the population lives below the poverty line—Obiang’s regime has reportedly misused the nation’s oil wealth for personal gain. His son, Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, epitomises this lifestyle. Known for his lavish spending, Mangue owns a fleet of luxury cars, a $30 million mansion in Malibu, California, and even a $500,000 customised Bugatti Veyron. In 2021, French courts convicted him of embezzlement and confiscated over $150 million in assets tied to corruption.

Similarly, Zimbabwe’s late President Robert Mugabe and his family enjoyed a life of luxury while the country’s economy crumbled. Grace Mugabe, known as “Gucci Grace,” gained notoriety for her extravagant shopping sprees, including spending millions on jewellery and luxury items, even as Zimbabwe faced hyperinflation and food shortages. This stark disparity between their public pleas for aid and their private indulgences has eroded trust in leadership and perpetuated the cycle of poverty in their nations.

Puppets of Western Power

The dependency of African leaders on Western powers has deepened over decades, perpetuating cycles of exploitation. For instance, Francemaintains a stronghold over its former colonies through the CFA franc, a currency pegged to the euro and controlled by the French Treasury. This economic arrangement severely restricts the financial autonomy of 14 African countries. Leaders who challenge this status quo, such as Mali’s transitional government under Assimi Goïta, face immense external pressure. In 2023, Mali expelled French troops from its soil, accusing France of fostering instability to maintain its influence.

The role of Western powers in supporting corrupt African regimes cannot be overlooked. During the Cold War, leaders like Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) were propped up by Western nations despite their kleptocratic rule. Mobutu embezzled billions while his country languished in poverty, a stark illustration of how Western interests have often prioritised stability and resource control over genuine development.

The Burden of Debt

Africa’s debt crisis continues to stifle its progress. As of 2023, the continent owed approximately $696 billion in external debt, with nations like Zambia and Ghana grappling with defaults. These debts are often the result of predatory lending practices by institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, coupled with mismanagement and corruption by African leaders. In Zambia, under former President Edgar Lungu, funds intended for infrastructure projects were misappropriated, exacerbating the country’s financial woes.

The assassination of leaders who sought to challenge the West’s economic dominance underscores the risks of defiance. Patrice Lumumba of the Democratic Republic of Congo, who advocated for economic sovereignty, was brutally murdered in 1961 with complicity from Western powers. Similarly, Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso, a vocal critic of neo-colonialism, was assassinated in 1987 under circumstances linked to external interference.

The Myth of Peacemaking

African leaders often position themselves as regional peacemakers while perpetuating or enabling conflicts that serve their economic and political interests. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a country rich in natural resources such as gold, cobalt, and coltan, has long been a battleground for proxy wars and covert exploitation, with Uganda and Rwanda playing significant roles.

Uganda’s Role in the DRC

Uganda’s involvement in the DRC’s conflicts dates back to the 1990s during the First and Second Congo Wars (1996–1997 and 1998–2003). These wars involved multiple African countries and were fuelled by competition over the DRC’s vast mineral wealth. Reports by the United Nations Panel of Experts accused Uganda of plundering resources, particularly gold, from the DRC during its military intervention. A 2005 ruling by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) found Uganda guilty of occupying parts of the DRC, committing human rights abuses, and looting natural resources. The ICJ ordered Uganda to pay reparations to the DRC, estimated at $325 million.

Rwanda’s Role in the DRC

Rwanda’s involvement in the DRC is equally complex and controversial. Following the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, the Hutu militia (Interahamwe), responsible for the genocide, fled to eastern Congo. Rwanda justified its military incursions into the DRC as necessary to neutralise this threat. However, its actions have often gone far beyond defence, extending into significant economic exploitation of the DRC’s resources.

A 2001 UN report accused Rwanda of systematically exploiting Congolese resources, including gold, diamonds, and coltan, through state-controlled enterprises and networks linked to the military. Rwanda’s backing of rebel groups like the Congolese Rally for Democracy (RCD) and, more recently, the March 23 Movement (M23) has further destabilised the region. M23, a rebel group operating in the eastern DRC, is widely believed to receive support from Rwanda, despite Kigali’s denials. A 2022 UN report provided evidence of Rwanda’s military involvement in supporting M23, enabling its capture of key towns in eastern Congo.

Human and Economic Costs

The consequences of Uganda and Rwanda’s involvement in the DRC are devastating. Over six million people have died as a result of conflict and related causes, such as disease and starvation, making it one of the deadliest conflicts since World War II. Millions more have been displaced, with the DRC hosting one of the world’s largest populations of internally displaced persons (IDPs).

Meanwhile, the illegal extraction of minerals has enriched elites and military networks in Uganda and Rwanda while leaving Congolese communities impoverished. According to Global Witness, up to 70% of the world’s coltan, a critical component in electronics, comes from the DRC. Much of it is smuggled through Rwanda and Uganda, where it enters international markets, often labelled as originating from these countries to evade scrutiny.

Historical Context of Exploitation

The roots of this exploitation can be traced back to colonial times. Under King Leopold II of Belgium, the Congo Free State was subjected to one of the most brutal regimes in history, centred on the extraction of rubber and ivory. The post-independence period saw little improvement, as external powers continued to exploit the DRC’s resources through alliances with corrupt local leaders. The Cold War exacerbated this dynamic, with superpowers supporting dictators like Mobutu Sese Seko in exchange for access to resources.

The pattern of external exploitation, often facilitated by neighbouring countries like Uganda and Rwanda, has perpetuated cycles of violence in the DRC. While these nations claim to act as peacemakers, their actions often undermine regional stability and enable the extraction of resources at the expense of Congolese sovereignty and development.

Some Of The Modern African Leaders Who Truly Care

Amidst a sea of corruption and self-serving leadership, a few African leaders stand out as genuine advocates for their people, prioritising development, transparency, and self-sufficiency. Among them is Ibrahim Traoré, the young transitional president of Burkina Faso, who took power in 2022. Traoré has focused on reclaiming Burkina Faso’s sovereignty and addressing the security crisis caused by extremist insurgencies. He expelled French military forces and championed agricultural self-sufficiency and social welfare, urging citizens to take charge of their nation’s defence and future.

The late John Magufuli of Tanzania also exemplified people-centric leadership. Nicknamed “The Bulldozer,” Magufuli fought corruption, cut wasteful spending, and redirected resources to healthcare and infrastructure. Similarly, Nana Akufo-Addo of Ghana launched the “Ghana Beyond Aid” campaign, which focuses on industrialisation and reducing dependency on foreign aid. Mokgweetsi Masisi of Botswana has also prioritised diversifying the economy beyond diamond exports while investing in education and technology.

A Call for Reflection and Action

Africa stands at a crossroads. The continent’s youth, who make up the majority of the population, must critically evaluate the past and present to chart a better future. Social media should not be a tool for deception but a platform for accountability. African leaders must prioritise their people’s well-being over personal enrichment and external validation.

The urgency for change cannot be overstated. As the world becomes increasingly interconnected, Africa must reclaim its narrative, demand accountability from its leaders, and build a future rooted in justice, innovation, and unity. Only then can the continent break free from the cycles of exploitation and dependency that have hindered its progress for far too long.

Aric Jabari is a Fellow, and the Editorial Director at the Sixteenth Council.